“Those who know you regret that you have grown old, but my regret is that you have grown tired. Hearts woven with zeal and honour do not age; their ageing lies only in fatigue and despair. Iran is without doubt dangerously ill — and the weariness of a physician like you is the surest sign of danger.”

— Mirza Malkom Khan, Little Hidden Booklet

The addressee of the lines above — the one who moved me enough to write this piece — is “His Excellency Moshir-od-Dowleh,” and I would very much like to believe that he is the same Moshir-od-Dowleh I am writing about here. During my research I became so familiar with him that I will call him Engineer Jafar, but you may continue to say His Excellency.

Engineer Jafar — the Mathematics Teacher

Fortunately, we have enough information scattered here and there about Engineer Jafar. For example, Ali Karimian’s article “Mirza Jafar Mohandes-bashi” in Issue 63 of Ganjine-ye Asnad is an excellent and comprehensive account of his life and his role as a trusted statesman of Amir Kabir. What that article barely mentions (beyond a passing reference) is precisely what concerns us here: Engineer Jafar, the mathematics educator.

I am interested in history only because of the people I write about, so I will mention the dates of Engineer Jafar’s life only to the extent that they help clarify his place in the history of mathematics education in Iran. And our story begins around the time when our dear neighbour Russia kept reaching into Iranian territory (from 1804 until the Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828). In the middle of these conflicts, Abbas Mirza (son of Fath-Ali Shah) realised how dire the situation was and how astonishingly advanced the Russians were. So he decided to send several people to Europe to return with science and industry.

He began in 1811 with two students — one of whom died abroad. Abbas Mirza persisted. In 1815, he sent a group of five to England. One of them was Mirza Saleh Shirazi, who became famous for publishing Iran’s first newspaper. So famous that people often write: “Mirza Saleh Shirazi and four others.” But here, we will write: Mirza Jafar-khan — and four others.

Our Mirza Jafar studied in England for four years and returned with the rest of the group in 1819 (1198 SH). He immediately began teaching, established an engineering school, and taught mathematics for four years — until the authorities decided they needed his political skills more than his mathematics. You can find the rest of that story elsewhere.

What matters to me are those four years in Tabriz — because the result was the first modern mathematics textbook written in Iran.

The Arithmetic of Engineer Jafar

In the introduction to his book, Engineer Jafar writes that he composed it for Mohammad Shah, at a time when the future king was still a child — “a tender yet robust young sapling” — interested in arithmetic and geometry. The engineering school in Tabriz was founded partly for this purpose. In “a short time,” skilled engineers and sharp calculators were trained there. Later, by royal command, he expanded the text, added rules of mensuration, and published it.

The preface dates the work to 1262 AH (1845 CE; 1224 SH) — twenty-six years after his return from England and six years before the founding of Dar-ol-Fonoon (1851 CE; 1230 SH).

A Necessary Comparison

At this point, I can’t avoid mentioning a book that makes me wince a little — Sheikh Baha’i’s Khulasat-ol-Hesab, the text that dominated arithmetic in Iran for nearly 250 years. Part recipe book, part philosophical treatise, it was the backbone of arithmetic instruction long before modern teaching entered the scene.

In contrast, Engineer Jafar’s book is the first Iranian arithmetic text written with the learner in mind. It includes explanations, worked examples, and — delightfully — exercises, which were called tanbih (“admonition”) at the time.

Historical Importance

Although written decades before Dar-ol-Fonoon, the book was published only six years before the academy opened. It does not seem to have been used there — likely because Engineer Jafar, like many supported by Amir Kabir, was sidelined after Amir Kabir’s assassination.

As a result, Dar-ol-Fonoon reinvented the wheel. Foreign instructors wrote new textbooks, Iranian students translated them, and original authorship was delayed for decades. And a certain habit became normal — so normal that its “unfortunate” nature faded from sight.

Later scholars such as Abdol-Ghaffar Esfahani — whom I admire immensely — produced mathematically modern works but, pedagogically speaking, sometimes took a step backward compared to Engineer Jafar.

Thus, Mirza Jafar-khan Moshir-od-Dowleh is the father of the modern, student-focused mathematics textbook in Iran.

The Pedagogical Wonders

This part is technical — but I ask you to read it, especially if you have children.

Think of how subtraction is commonly taught today: the take-away view — we have some objects, we remove some, and ask how many remain. Simple, but limited. Many real problems rely on the distance view: how far apart two numbers are (for example, two ages).

Current primary school books in Iran are full of the take-away view and only occasionally touch the distance view, even though the latter becomes crucial later in students’ mathematical development.

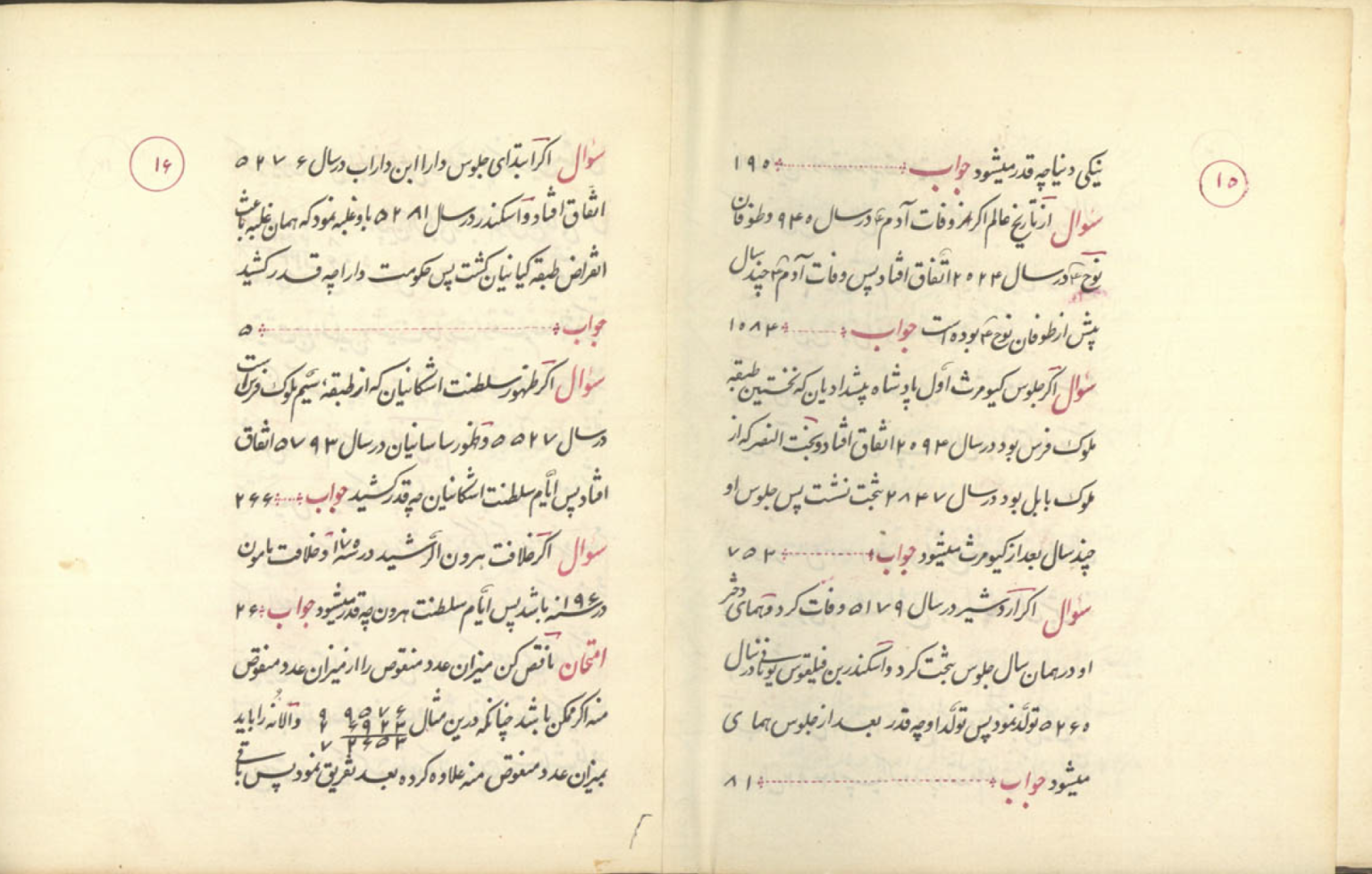

Now look again at the two pages from Engineer Jafar’s book.

In 1845, he was already doing it correctly — integrating both views.

Conclusion

The modern story of mathematics education in Iran quietly begins with Engineer Jafar.